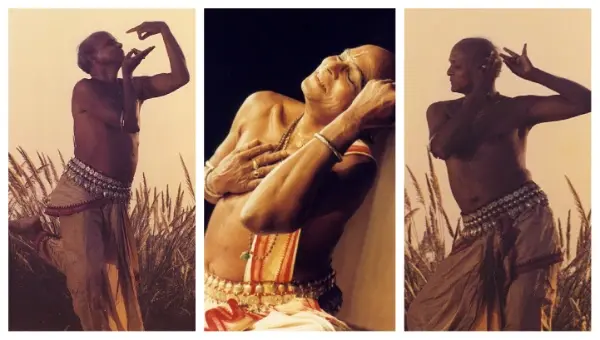

Renowned physicist Fritjof Capra, author of ‘The Tao of Physics’, described witnessing Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra’s performance alongside disciple Sanjukta Panigrahi in Mumbai in 1980 as a transcendent experience: “To see this oddly beautiful old man float across the stage on swirling, twisting, flowing movements, the candles flickering all about him, was an unforgettable experience of magic and ritual. I sat there spellbound, staring at Guruji as if he were some being from another world, a personification of archetypal movement.”

For the scientist-thinker, it was nothing less than a profound encounter with magic and sacred ritual — an experience that seamlessly connected the rational with the mystical.

Today, we commemorate the centennial birth anniversary of Guruji, the iconic dancer and teacher widely recognised for revitalising and modernising Odissi, one of India’s most prominent classical dance forms. Although official records indicate his birth year as 1926, his biographer Ileana Citaristi suggests in her book ‘The Making of a Guru: Kelucharan Mohapatra, His Life and Times’ that he may actually have been born in 1924. In any case, his rise from modest origins to becoming the pivotal figure who shaped contemporary Odissi dance continues to be one of the most uplifting and remarkable stories in India’s cultural history.

Guruji is widely regarded as the greatest global ambassador of Odia culture. He almost single-handedly revived and elevated Odissi dance — a classical form rooted in the ancient temple traditions of Mahari (devadasi) and Gotipua (young boys performing as women to honour Lord Jagannath) — from near extinction to international acclaim. Starting as a young attendant and performer in Mohan Sundar Dev Goswami’s Rasa Leela troupe, where he learned acting, singing, stagecraft, and percussion, he rose through relentless dedication to become the undisputed maestro of Odissi.

In a deeply significant way, his life and legacy represent a true revolution. He didn’t merely preserve tradition; he transformed it with extraordinary vision and courage. Drawing from ancient sculptures, temple texts, Gotipua fluidity, and Mahari grace, he restructured Odissi into a refined classical form while staying deeply authentic to its spiritual core. With an intimate understanding of Odissi tradition, he boldly reinvented its

authenticity from within, enriching it with technical precision, evocative abhinaya, and a sculptural aesthetic that turned the dancer into a living embodiment of temple carvings brought to life.

For over five decades, Guruji nurtured some of India’s finest dancing talents. Among his prominent disciples — such renowned figures as Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kumkum Mohanty, Sonal Mansingh, Madhavi Mudgal, Protima Bedi, Sharon Lowen, and his son Ratikant Mohapatra — continue to propagate his distinctive gharana (style) across the globe.

He created an impressive repertoire, comprising over 200 solo pieces and around 50 dance ballets, many in collaboration with great musicians like Pandit Bhubaneswar Misra.

Yet, what remains profoundly moving and often less discussed are his own rare performances as a dancer. Even in his later years, no one could rival the serene divinity he infused into physical expression. His movements were fluid poetry in motion, embodying an effortless elegance that transported audiences to another realm. The New York Times once described his performance at the age of 75 as sculptural, sensual, touching viewers with the subtlest raised eyebrow or modest gesture. He was a living bridge between the ordinary world and the timeless realm of beauty, bliss, and devotion — a moving prayer, in his own words: “Odissi is not a mere dance form to entertain people but to inspire and elevate.”

Yet another often overlooked facet of his genius was his mastery over music and rhythm. A virtuoso on the Mardala (the traditional Odissi percussion instrument) and Tabla, he created magic with each stroke and twist capable of evoking spiritual ecstasy in the listener. He composed music for countless dances and, in a 1975 paper titled “The Use of Music and Rhythm in Odissi Dance,” argued that rhythm is an integral part of the artiste’s spiritual self, not mere accompaniment.

As one close friend beautifully put it: Every Odia, and indeed every admirer of Indian classical arts, should aspire to bow at the feet of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra — whether he still walks this earth or lives forever in the hearts of millions. His enduring legacy continues through institutions such as Srjan (established in 1993 alongside his wife, Laxmipriya, and son, Ratikant), the Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Odissi Research Centre, as well as annual tributes such as the Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Award Festival and centenary celebrations featuring special performances across Odisha.

Pranam Guruji! Your dance was a prayer, your life a revolution, and your spirit an eternal flame illuminating Odissi and Odia culture forever.

(The views expressed in the article belong to the writer and not the organisation, its affiliates, or employees)