On transfer of my father from Keonjhar, I joined Ravenshaw Collegiate School, Cuttack, in Class-VI in the middle of an academic session. I was assigned a seat next to Srimoy Kar, who by that time was famous as a child star in Odia films. He very graciously decided to mentor a rustic boy from a lesser town.

In a few days, Srimoy took me to his house, where I met his father Pranabandhu Kar, an eminent educationist and respected Odia litterateur. He was pleasantly surprised, “You are the son of Rajendra! I know your father since he was almost your age. He addresses me as “Prana Mamu” (maternal uncle). Ask your father he will tell you everything.” When I told my father he got very excited, and told me “Prana Mamu was Inspector of Schools at G. Udaygiri, where your “Jeje” (paternal grandfather) was posted as an Excise Officer and we were neighbours.” The very next day my parents visited their place to revive and remove the cobwebs of an emotional relationship.

Thereafter, the two families met at least once every week. Srimoy was the youngest among five siblings, four brothers and a sister. Punpun bhai, a maverick and flamboyant boy who was just a few years older than us, would often come up with his big-brotherly advice. He was also a very good painter. I remember him painting a beautiful cover page for our class magazine. (In our school each class used to come up with hand-written class magazines.) Unfortunately, he died very young while swimming in the sea.

For us Srimoy’s eldest brother, Gitimoy Kar (Gitu bhai) was an enigma. He lived in the USA and Srimoy would amaze us by telling stories about him. He was an immensely eligible bachelor. During his visit to home sometime in 1971, my mother took on herself the responsibility of finding a suitable bride for him. She vigorously pursued one proposal and personally got involved in it. Due to some reasons, it did not materialise, which led to a serious misunderstanding between the two families and a blossoming relationship suddenly collapsed. Not that there was any showdown, but the temperature went well below freezing point.

After school, I joined Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, and Srimoy went to Puri. We got busy in our respective academic careers and later professional pursuits and lost touch with each other. In the late 1980s, I met Srimoy briefly on a few occasions, when he was flourishing as a journalist. We actually revived the warmth in our friendship on my return to Odisha after a deputation to Government of India. I was posted in Bhubaneswar. Since I was outside for several years, I was almost an alien in the city. In contrast, Srimoy being the Resident Editor of ‘The New Indian Express’, Bhubaneswar edition, was a Page-3 personality. Again, after three decades, Srimoy took upon himself my mentorship in the social circles of Bhubaneswar.

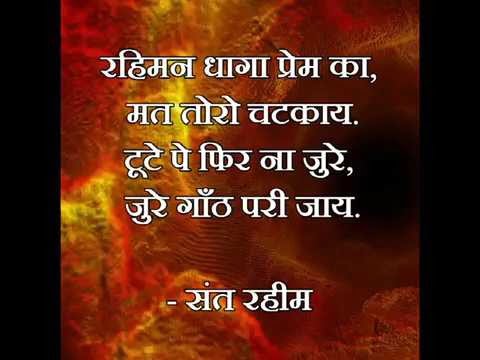

Pranbandhu Kar passed away just a few days before I returned to Bhubaneswar in April 1998. My parents became extremely disturbed when we discussed this. My father said, “I was so stupid that my flimsy ego got the better of me and allowed such a sweet relationship to go sour. Now that Prana Mamu is no more, the only option before us is just to bitterly regret.” Then he recited a ‘doha’ (couplet) by Rahim, the legendary poet of the medieval period, which means, “Relationship of love is like a string. One should never break it; once it is broken it would never rejoin, if at all it rejoins the knot would always remain.”

My father had two sisters, one elder to him, another younger. His love for his sisters was so intense that it sometimes incited jealousy in my mother – a normal reaction in a middle-class family. Due to several communication gaps, the relationships got strained and they didn’t have time to discuss and sort it out. His younger sister died young because of cancer. She carried with her a slew of suppressed complaints, which she would otherwise have fussed over before her brother. And he understood all those unspoken words but preferred to silently endure the pain. By the time my mother wanted to clear up the misunderstanding with her elder sister-in-law, it was too late. She was not able to talk due to a paralytic attack and my mother passed away a few days later. And my father was left in the lurch after the death of the three women he loved most.

He has poured his heart out in his autobiography. It makes very intense and emotional reading. He wrote the book towards the last part of his life when my mother, his sisters and many of his relatives were no more. He had become very lonely. He discussed his regrets in life with me on several occasions, mostly when he was in a pensive mood. He felt he had ignored personal relationships on the altar of professional commitments. “During my service period, I devoted my entire time and energy to official work and as a result neglected my immediate family, what to speak of other relatives. I don’t know what imprint I left behind due to my professional commitments, but neglecting personal bonds has definitely created a vacuum in me. As time is passing by, I realize, I am gradually slipping into oblivion; irrelevant for the profession I devoted my entire life to and a blurred presence in the extended family,” he said.

The only thing that kept him vibrant and kicking was his interest in the field of literature and culture and his intense desire to remain self-dependent. But he carried to his grave the regret that he should not have allowed trivialities to affect his relationships.

I would like to end by quoting Allen Lazar, “If you love and care for me, tell me while I am alive. Don’t send me flowers and write a poem when I am dead.”

ADVERTISEMENT