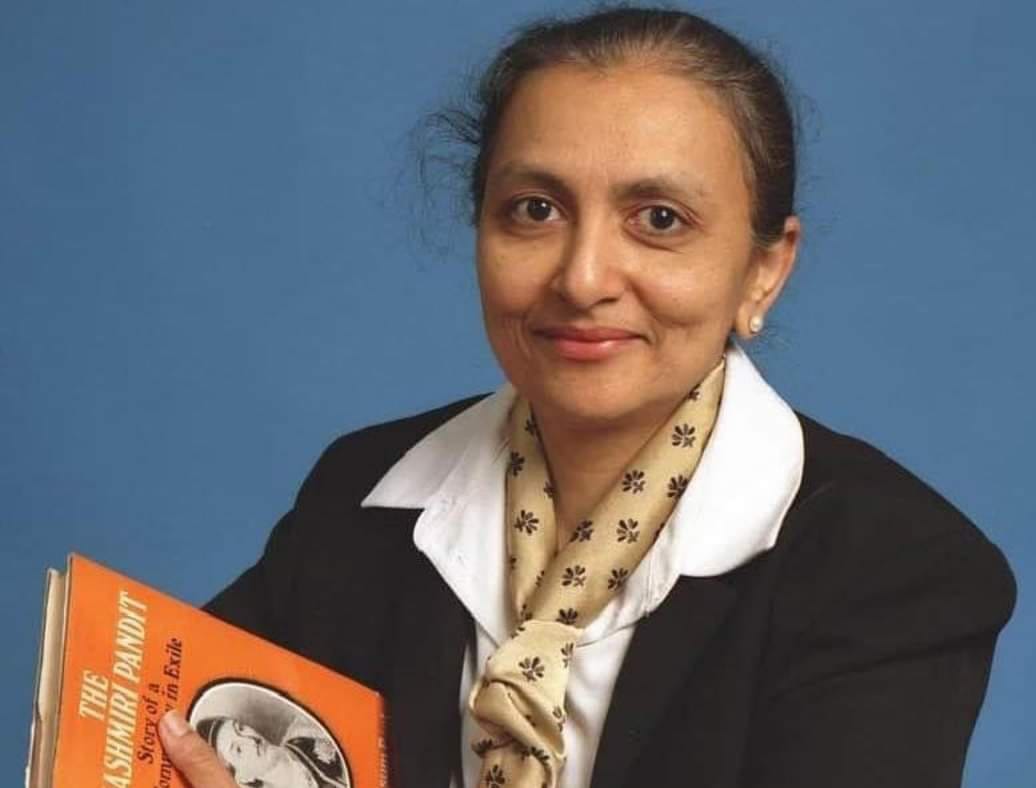

Kusum Pant Joshi’s book has a foreword by Lyn Innes, Emeritus Professor of post colonial literature, University of Kent. Focused on colonial history and its determinants, it is a well-researched book, containing pertinent illustrations, and is written in a warm, effortless style.

The book exposes caricatures of celebrities of South Asian and African origins in ‘Vanity Fair’ magazine, which was a fashionable weekly when British imperialism across the globe was at its height. We are led into noting how visiting celebrities from British colonies were mis/represented by their imperial masters and how the subaltern reacted to the political, social and cultural assertions to which they were subjected.

Cartoons are an integral component of journalism. The writer has shown how ‘Vanity Fair’ caricatures translate into a historical record of the socio-political and cultural climate of the time and how they communicate the ecosystem of an era. Generally post colonial writing challenges what Edward Said refers to as cultural imperialism. Without making it obvious the writer succeeds in making her readers reclaim and rethink the history and agency of people subordinated under imperialism.

There is a list of 28 African and Asian celebrities with their date of appearance in London between 1868 and 1914. Joshi’s effort is directed at bringing the caricatured individuals to life by placing them in their historical context and assessing their importance and contribution.

The first in the list is Mansur Ali Khan, Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha, whose caricature in ‘Vanity Fair’ is offending. The editor of the magazine himself asserts that it is a living monument of English injustice and that the Nawab was a victim of British misrule and greed. On the other hand, the representation of Sir Salar Jung is supposed to be a compliment for the excellent service he had rendered to the English in suppressing the ‘mutiny of 1857’. The British bias is clearly evident here.

There is also a substantial delineation of Chinese history. It is difficult to overpower an ancient civilisation which clings to its cultural roots and defies absorption by a foreign culture. But Kuo Sung Tao, a Chinese scholar, was caricatured exactly as he appears in contemporary photographs. This is because he was open to negotiations and resorted to diplomacy in order to successfully deal with western powers.

David Sassoon’s pro- British leanings helped him to expand business. His caricature is therefore a dig at his English or European pretensions as he eschewed his Arab robes in favour of the trappings of the gentlemen of British upper classes. Likewise, the book mentions some Egyptian, Indian, Japanese and Korean celebrities whose caricatures feature in the magazine, some of them offensive, some of them true to life, depending on their willingness to adopt and adapt to British cultural supremacy. As the writer affirms, there is an ‘Orientalist’ bias against the ‘Other’ in the British assessment of the characteristics of non-British celebrities.

What the reader may conclude is that the British everywhere used their prominence to destroy everything that posed a threat to vital British commercial interests. But there are also indications that bonding between the East and the West seems possible on the basis of common human parameters.

The biographical sketches in the book include essential details about the role of the featured celebrities as soldiers, administrators and diplomats. The complexity inherent in the interrelationship of race, class and gender is worked out as clashes occur between different civilisations and cultures. The book is an important addition to post colonial history. It is definitely of interest to the general reader who is serious about knowing the past.

The title of the book has a question at the end which I believe is very suggestive. It engages the reader at a deeper level, making them pay attention, look behind and beneath what has been written, and learn crucial lessons about our colonial past.