Within a week of the Beirut blast, which killed nearly 200 and wounded over 600 people, the Lebanon government stepped down. Prime Minister Hassan Diab said the blast was a “disaster beyond measure” and announced his resignation.

Lebanon was already in the midst of its worst economic crisis in decades and struggling with rising coronavirus cases, even as the government was plagued by accusations of corruption and gross mismanagement. The blast turned out to be the last straw.

Political resignations are all about accountability at the highest levels of governance. Decisions to step down are taken either to take the moral high ground or use as a strategy to push rivals on the backfoot.

Even India has seen politicians stepping down on moral grounds after some disaster or the other. Here’s their story:

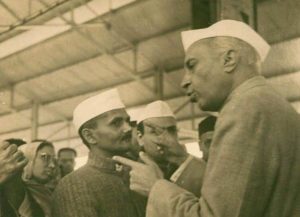

Lal Bahadur Shastri

As Railways Minister under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri tendered his resignation on two occasions. The first time he tendered his resignation was after a major railway accident in Mahabubnagar, Andhra Pradesh, in August 1956 when 112 people died. He was, however, persuaded by Nehru to continue.

As Railways Minister under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri tendered his resignation on two occasions. The first time he tendered his resignation was after a major railway accident in Mahabubnagar, Andhra Pradesh, in August 1956 when 112 people died. He was, however, persuaded by Nehru to continue.

Following another railway accident in Ariyalur, Tamil Nadu, three months later, when 144 were killed, Shastri submitted his resignation and pleaded for ‘early acceptance,’ writes his biographer Sandeep Shastri.

According to his fellow Parliamentarians, Shastri was not responsible for the accident which was caused by a technical failure and was thus the responsibility of the Railway Board. But despite efforts by Nehru and his fellow-MPs to dissuade Shastri, the latter was adamant and had his way.

Resignation of other Railways Ministers

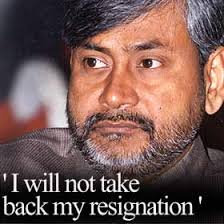

Suresh Prabhu offered to resign as Railways Minister on August 23, 2017, taking moral responsibility for two train derailments in a span of four days — Kaifiyat Express and Puri-Utkal Express. Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked him to wait, but Prabhu stepped down next month.

Suresh Prabhu offered to resign as Railways Minister on August 23, 2017, taking moral responsibility for two train derailments in a span of four days — Kaifiyat Express and Puri-Utkal Express. Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked him to wait, but Prabhu stepped down next month.

Nitish Kumar resigned as Minister of Railways, owning responsibility for the Gaisal train disaster in Assam in August 1999. The accident resulted in 290 deaths.

Nitish Kumar resigned as Minister of Railways, owning responsibility for the Gaisal train disaster in Assam in August 1999. The accident resulted in 290 deaths.

VP Singh

When Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi shifted VP Singh from the Finance Ministry to Defence Ministry in January 1987 because of his relentless tax raids that put many industrialists and businessmen to jail, not many knew what was happening.

When Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi shifted VP Singh from the Finance Ministry to Defence Ministry in January 1987 because of his relentless tax raids that put many industrialists and businessmen to jail, not many knew what was happening.

A few months prior to his resignation, Singh had authorised his officials to hire a private American detective agency, the Fairfax Group, which discovered that wealthy Indians had stashed their black money in foreign banks operating across different tax havens. By coincidence or design, Fairfax went after Prime Minister Gandhi’s friends and acquaintances as well.

After getting a lot of stick from his party colleagues, VP Singh tore apart Gandhi’s claim of no middlemen in defence deals concerning the Indian government and that if any arms supplier hired one, he would be disqualified from the bidding process. Based on a secret telegram he received from the Indian ambassador in then West Germany, VP Singh found out that “that an agent was paid a commission for the purchase of two submarines from HDW,” writes veteran reporter Inder Malhotra. Singh ordered an inquiry, and before Rajiv Gandhi could react, newspapers reported the story following morning. Singh eventually resigned and was soon expelled from the party.

TT Krishnamachari

In 1957, India was witness to its first major political scam, leading to the resignation of Finance Minister TT Krishnamachari.

In 1957, India was witness to its first major political scam, leading to the resignation of Finance Minister TT Krishnamachari.

According to a New York Times report, over the next few months the public-sector Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) had bought 1.24 crore, or 12.4 million rupees, worth of fraudulent stocks in six companies owned by Haridas Mundhra, a Calcutta-based businessman. The investment was the largest that LIC had made in its short history, but contrary to regulations, its investment committee had not been consulted on the decision.

According to veteran business reporter Sucheta Dalal, there was evidence that Mundhra was bleeding the companies and siphoning off large chunks of money, while simultaneously operating in the market and rigging prices as cover to his own sales of these scripts.

The New York Times report further stated ostensibly, the shares were purchased by LIC to stabilize the market; in reality, they had the effect of bailing out a suspect businessman, and the puzzling order to do so seemed to have come from within the highest reaches of government.

An inquiry was ordered by Prime Minister Nehru, which was headed by former chief justice MC Chagla. He submitted his report in less than a month. The hearings of the Chagla commission were held in public with massive crowds attending. When Chagla submitted his report, Krishnamachari resigned on February 18, 1958, even though the commission had said nothing about his personal complicity.

VK Krishna Menon

Some political figures are destined to be remembered for their failures more than their successes. Whether that’s fair or not is a discussion for another day. As a statesman, Krishna Menon had the unique ability to cut through the fog, identify core concerns and deliver solutions.

Some political figures are destined to be remembered for their failures more than their successes. Whether that’s fair or not is a discussion for another day. As a statesman, Krishna Menon had the unique ability to cut through the fog, identify core concerns and deliver solutions.

As India’s representative to the United Nations, he almost facilitated the opening of diplomatic channels between China and the United States, played a role in bringing the Korean War to an end and was deeply involved in the resolution of the crisis emanating from the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. As Defence Minister, he played a critical role in the annexation of Goa from Portuguese colonialists in 1961, and admonished any criticism by Western powers for India’s actions as “vestige(s) of Western Imperialism”.

However, his downfall came the following year after the India-China War. Following a crushing defeat at the hands of China, Menon came in for sharp criticism from within and outside Parliament for his ineffectiveness and poor handling of India’s military preparedness. He eventually tendered multiple resignations, the last of which was sent to Prime Minister Nehru on November 7, 1962.

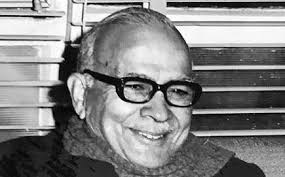

Keshav Dev Malviya

A chemical engineer by trade, Malviya was deeply involved in the anti-British struggle, particularly during the Quit India Movement when he was engaged in organizing anti-British activities and setting up a clandestine broadcasting unit. Post Independence, Malviya played a stellar role in building up India’s domestic oil industry much to the chagrin of foreign oil multinationals. But everything changed in 1963.

A chemical engineer by trade, Malviya was deeply involved in the anti-British struggle, particularly during the Quit India Movement when he was engaged in organizing anti-British activities and setting up a clandestine broadcasting unit. Post Independence, Malviya played a stellar role in building up India’s domestic oil industry much to the chagrin of foreign oil multinationals. But everything changed in 1963.

“Keshav Dev Malviya had done much, as Minister in the central Government, to develop oil prospecting in India without allowing foreign companies to dominate the field. Now it became known that he had requested a private firm to assist a Congress candidate in the elections. The sum involved was relatively small and Nehru believed that the firm had derived no kind of benefit, direct or indirect, in return for such assistance. But the issue could not be shirked,” writes Sarvepalli Gopal in ‘Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography’.

Nehru asked a Supreme Court judge to conduct a private inquiry, which found some substance to the allegations against Malviya, who resigned. “So, Nehru, acting solely on his own, took the right step of reluctantly accepting Malviya’s resignation; but he was unhappy about it for he was convinced of Malviya’s honesty and probity,” adds Gopal.