On the occasion of 74th Independence Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said economic growth and development should be the focus of the country but humanism should not be sidelined in the process. This brings into focus the issue of humanism at a time when there is a raging debate over the choice of faith and nationalism, thereby bringing to my mind Rabindranath Tagore’s 1909 famous novel Gora.

Gora is perhaps the most popular literary character Tagore created in his novel by the same name. Gora comes to the fore because of his metamorphosis from a staunch Hindu to a liberal. He breaks out of the prison created in his own mind by himself and the nineteenth century predominant Brahminical society.

Gora is an idealist. He is also an optimist. He dreams of the utopian ‘Bharat’. He is compassionate towards the downtrodden and presumes that all evils of the society can be uprooted if everyone embraces Hinduism. He firmly believes Hinduism can be the saviour for all other religions. Gora is assertive and egoistic, when it comes to his staunch religious beliefs. Gora is the product of a Bengal, which was torn between conservative Brahminism and emerging Brahmo beliefs that increasingly drew from westernised liberal reforms.

Naresh Mitra and Shukla Mitra adapted Gora in their films by the same name released in 1938 and 2015 respectively. In 2012, Somnath Sen directed a 26-part series based on the novel. Originally, Tagore wrote the novel episodically in 24 parts. Among the other notable adaptations is Prakash Belawadi’s Kannada play.

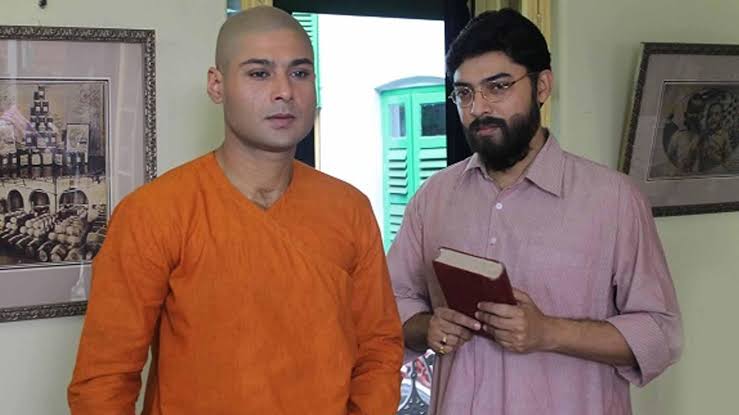

In his novel, Tagore describes Gora: “He was nearly six feet tall with big bones and fists like the paws of a tiger. The sound of his voice was so deep and rough that you will be startled if you suddenly heard him calling.” His professors named him ‘snow mountain’ as he was ‘outrageously white’. However, we don’t see such a fair Gora in the film adaptation of either Naresh or Shukla. Both don a medium fair Indian complexion – not reminding us of the Irish man and English woman parentage of Tagore’s Gora. Shukla’s Gora (played by Rizaul Haque) is a bald young man – almost monkish – in an impressionistic Brahminic saffron attire almost throughout the film. However, Naresh’s Gora (played by Jiban Ganguly) has prototype Bengali male features: long nose, big eyes and, in contradiction to Shukla’s Gora, has a rich tuft of hair on his scalp that sometimes looks like a wig.

We see a more light-hearted Gora in Naresh’s movie compared to one made by Shukla – an occasional smile adorns the former’s face either for his friend Benoy or mother. We see a more serious Gora in Shukla’s flick. However, Naresh’s Gora becomes much more agitated and assertive when he is preaching against the Brahmo rituals and beliefs to Benoy, having a heated debate with Haran babu or when he is trying to break off Shashi’s marriage with Benoy. He is more volatile. Shukla’s Gora remains more stoical, with rare occasional flares of temper when it is required to save a woman’s modesty (even though he is a conservative Hindu and she a Muslim woman) or other such reformative actions.

Gora, in the 1938 film, is extremely expressive and aggressive whereas the 2015 version shows the protagonist as a rather inexpressive character and more gloomy. Both, however, show their open contempt for Brahmo Samaj and its reforms. The incident where Gora meets a Hindu villager taking care of a Muslim orphan becomes a turning point in his life. He tries to question the meaning of humanity and religion. Naresh’s Gora becomes agitated, whereas in Shukla’s film he recedes into his thoughts – debating over what is right and wrong. Another interesting juncture in the book and the movie comes when Gora gets to know the reason why his father does not want him to touch his feet after bathing. He is shocked that he was not born a Hindu but his parents adopted him from a mixed parentage (English and Irish).

The character of Gora is popular because he is able to understand and appreciate the true meaning of nationalism. At first, he believes if anyone follows any religion, including Brahmo Samaj practices, other than Hinduism, it means going against India and not being a part of the country. Gora alludes to Hinduism as India’s only religion that can cause redemption of people from all other faiths. Finally, he is able to see the liberal ideas and practices of other religions, especially of the Brahmo faith. He understands that humanism stands above all religions. And his soul gets awakened.