One reads books for two reasons: enjoyment and enlightenment. There are scores of books, even hundreds if one is the book reading type, which one reads during the course of one’s active life. But how many of these can vouchsafe the two life-giving qualities? How many of these can grant us the pure enjoyment that we got from books as children? True, enlightenment is not the idiom in which childhood spoke, but surely enlightenment, or let us call it by its familiar name of wisdom, lurked inside enjoyment, when as children we listened with delight and profit to Abolokara Kahani or Panchatantra tales or, for that matter, Winnie the Pooh or Cinderella.

Perhaps the Baconian formula may help in sorting out the categories into which books of the world may fall: the grazers, those for tasting, the sliders, those for swallowing, and the plodders, those for chewing and digesting. One may want to conclude that the few books which are meant to be chewed and digested are the true guarantors of enjoyment and enlightenment. But there is a problem. The metaphor of strenuous mastication and gastric labour that Bacon invokes seems to jar against the delicious smoothness and well-oiled flow of the childhood imagination.

The great books of Bacon bring to mind the perspiring scholar at his desk, who burns the midnight oil. These are a far cry indeed from those eternal tales which we lovingly and effortlessly savoured as children and would do so again as adults with a childlike hunger if they were to be resurrected in their modern avatars. One such modern avatar is Antoin De Saint-Exupery’s 1945 book Le Petit Prance (translated into English as The Little Prince by Katherine Woods and into Odia as Rajkumar by Chittaranjan Das).

The Little Prince tells us the fascinating story of the adult narrator’s meeting with a very small person who is the sole inhabitant of another planet, and, who calls himself the little prince. The prince tells him about his encounter with humans, which is always frustrating, and his encounter with birds, animals, reptiles, trees and flowers, which is always enriching. And he in turn passes two of the best secrets of the good life to the narrator who has, since his childhood, been in holy dread of the grownups. The two secrets are to do with learning the wordless language of the universe and seeing with your heart, that is, to ‘see it feelingly.’

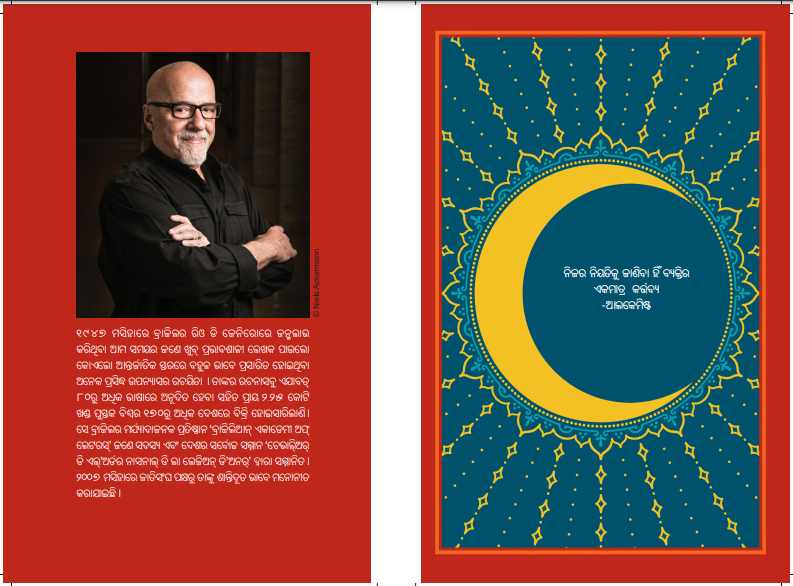

Mankind is in need of periodic revivals of these simple parables. And as if in answer to such a prayer issuing from deep within the human soul there came in 1988 Brazilian writer Paulo Coelho’s great modern parable The Alchemist, with an English translation by Alan R. Clarke coming out in 1993. The Alchemist took the world by a storm with its simple story of the Andalusian boy Santiago who goes half way across the world to the Egyptian pyramids in search of buried treasure only to return home, with the realization that this treasure always lay in his backyard. The Alchemist provides a much stronger reinforcement to the two messages of the little prince, which Coelho recasts as ‘the principle of favourability’ (P. 54) and the universal language of the heart that all things speak wordlessly. Coelho says in his preface that The Alchemist is a symbolic recounting of the discovery of his own destiny as a writer. He thought that the desired object, namely his power to write, lay outside himself and far away, so he set out on his globe-trotting journey to achieve it. But what was his surprise when he found that this treasure was always inside him, waiting for the opportune moment to be unlocked. He did not write off the journey, because the journey provided him – just as it provides his fictional alter ego Santiago in his meeting with the king, the owner of the crystal glass shop owner, Fatima and finally the alchemist- with the opportunity to do his soul searching. But The Alchemist’s lesson is not for the writer alone; it is for everyone who is seeking to find himself. The only thing that is required is that he follow his heart.

But why talk of The Alchemist now, which is by now a very familiar book – and even a dated one, some might say? There is a very good reason. A brand new Odia translation of the book has just been published by a national publishing house. More to the point, the Odia rendition of The Alchemist has been the happy cause of this reviewer’s encounter with a wonderful book which he otherwise would never have read, mistakenly thinking that it was in the same league as scores of money-spinners of our time – books such as You Can Win, The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari – that masquerade as self-help and motivational books. Kudos to the translating duo, Somesh Mahapatra and Manisha Mishra, for this change of mind that they inspired in me. I read the book first in Odia and then in English and I have to say this. If the English translation is like a window pane, clear and transparent, the Odia rendering is like the play of stained glass.

Here is one example: ‘the principle of favourability’ is translated into Odia in one place as ‘sahayaka tatwa niyam’ (p. 46) and in another place as ‘anugraha pradarshana niyam’ (p. 47). But my favourite is this sentence from earlier on in which Santiago writes about what he thought tied his father down to the barn for his entire life: “… anek barsha tale samanya basagrasa jogadibara bojhare nirabare tanka rajya bulibara icchaku daman kari mana gahirare poti pakaithile” (p. 9). Now the English translation of the same is as follows: “ … despite his father’s having had to bury it, over dozen of years , under the burden of struggling for water to drink and food to eat, and the same place to sleep every night” (p. 10). The economy of the Odia usage is stunning. The compound word in Odia, one that is underlined, disposes of so much of excess baggage in English, literally the whole of last part of the English sentence beginning with ‘under the burden …’

Alchemist then brings into Odia a modern parable and not just an international bestseller. A special attraction of this translation is the presentation in Odia of an interview that Laura Sihen did with Paulo Coelho. This is an event.