On today’s date, five years back—30th July 2015—Odias did something which was unimaginable just a couple of years back. They more or less convinced the world that what they have known so far as the ‘Bengali’ rasagola was, after all, an Odia invention. It originated in the temple traditions of Shri Jagannath Mandir in Puri centuries ago.

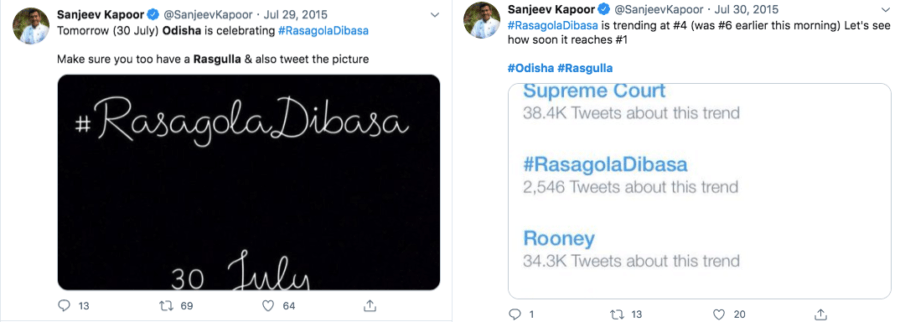

This was done by some Odia Twitter users—who did not even know each other—by collectively planning what they called Rasagola Dibasa, and tweeting the hashtag #RasagolaDibasa, which trended nationally in Twitter in top 10 position that day for a long time. Many celebrities outside too Odisha joined in and supported the Odia tweeple in their endeavour. Among them was celebrity chef Sanjeev Kapoor who not just appealed to all to celebrate Rasagola Dibasa and tweet using the hashtag, but also joined the celebrations when it started trending in Top 5.

What happened after that is history. There was huge backlash from traditional media, dominated a lot by Bengalis. Though it was not planned as a Bengali-vs-Odia debate by the Odia Twitter users, it soon turned that way, even as many media houses did their own research and vindicated the stand taken by Odias. Many tried to find a middle ground. What followed after that is a long battle for GI and a lot of debate in all forms of media, research, and efforts at governmental levels. That is a different story.

This was the first instance—at least for Odias—to effectively use new interactive media to propagate something which would never have been possible by just relying on traditional media channels. And through that they were making a strong statement of identity. Along with Odissi, Konark, Jagannath, Rasagola also became a symbol of Odia identity outside Odisha.

The search for Odia identity

While the New Media—global, interactive and instantaneous—redefines how identity assertion is now possible, the RasagolaDibasa example being just one of them, the search for identity has been there since early days of history.

The existence of the land of Kalinga (with a race also known as Kalinga)—which roughly pertains to the modern day Odisha—has been well-recoded in modern history. Kalinga War—and the transformation of Ashoka—is known to school kids.

Kalinga also finds significant mention in Hindu itihasas, like Mahabharata. In the battle of Kurukshetra, king of Kalinga, Shrutayu, according to the epic, fought on the sides of Kauravas. The heroics of Kalingas, especially with their fight with Bheema, the 2nd of the Pandavas, is well-described. The epic also mentions the king of Odra who had sent gifts for Yudhisthira when the latter was performing Rajasuya yagna.

But mere recording of the history of a place and/or a race, or a narrative on its qualities per se, is not of significant interest to study of its identity. What makes it a serious question on identity is the claim by many modern historians that Kalingas were a significant pre-Aryan tribe, different from Dravidians. While the Odias of modern day are a mixed race, the claim for that unique racial identity is very much there and any discussion on Odia identity cannot ignore that.

The next question/issue/crisis of identity came when the Kalingas—and with no mention of a king or leader—lost to the Army of Ashoka, after a prolonged battle where millions of people died, on both sides. But even that comes with a silver lining, as it is that war—and a Buddhist monk from Kalinga—which transformed Ashoka from Chandashoka to Dharmashoka and arguably changed India’s history. While some of the theory—about Kalinga’s ‘defeat’ and Ashoka’s acceptance of Buddhism in Kalinga—has been questioned in recent scholarship, that nevertheless remains a strong identity statement for a land and its people—where peace is the predominant spirit, despite unmatched valour.

The next major milestone in history of Odia identity was a high point that occurred merely a century after the Kalinga War—a war that had devastated the land and the people. A king of Kalinga, Kharabela (written outside Odisha as Kharavela), not just rebuilt Kalinga with a lot of development work and significantly patronized performing art, he attacked Magadha to bring back the Kalinga Jina statue taken forcibly by the Nanda rulers of Magadha. While doing so, he showed glimpses of greatness by choosing not to side with foreign invaders but attacked Magadha only after chasing them away. Arguably that was the first assertion of Odia (if one can call it so) identity. Another great thing Kharabela did—and which is still an ethos in Odisha—is he patronized all existing religions—Buddhism, Brahmanism, and of course, Jaininism, which he followed. The Udayagiri caves at Bhubaneswar are a testimony to that fact.

Kharabela’s time was also important for what is now being traced as the origin of Odia script and language—a defining attribute of identity for an ethno-linguistic community.

It is also around that time that Bharata’s Natyashatra wrote explicitly about the Odra-Magadhi variation of dance, which is supposed to be the distant ancestor of the present day Odissi—which, outside Odisha, and even outside India, is Odisha’s most well-known identity today.

The next major point of Odia’s search for identity came with Ganga King Anangabhima Deva declaring himself to be a Rauta (deputy) of Lord Jagannath. That is the beginning of accepting Jagannatha as the most important identity for Odias.

Since then, at different phases, Jagannatha has been used as a symbol of Odia identity—to internally unite them, to assert their identity and in fact, to construct the Odia identity as an assimilative one. In Odisha, people of different faiths worship Lord Jagannath. In fact, so strong is this assimilative ethos—Jagannath means Lord of the Universe—that there have been strong rebuttal by many common Odias to portray Jagannath as another Hindu deity in the recent political discourse. In today’s atmosphere of communal divide, the world was stunned to see that a Muslim from Odisha was one of the first to appeal in the Supreme Court against the decision to stop Ratha Jatra this year, due to the pandemic.

Kapilendra Deva, the first king of an ethnically and linguistically Odia origin, used Lord Jagannath’s name to legitimise his capture of power dethroning Shesha Bhanu Deva, the last ruler of Odisha from the Ganga dynasty.

But more than military might—which Kalinga earlier too was known for—it is the rise of Odia language in the Gajapati period that makes a marked beginning of Odia identity statement. After Odia made it to the royal courts, it flourished as a language of learning, literature and art.

The first major written work in Odia—Odia Mahabharata—was also written in this period by Sarala Das called Adikabi (the first poet). The Sarala Mahabharata was not just in Odia language but strongly Odia-ized Mahabharata, even making Yudhisthira marry Suhani, the daughter of a local trader in Jajpur, Hari Sahoo.

The other defining work of that period which went a long way in giving Odias an identity was Odia Bhagabata by Jagannath Das. It is said Das’ mother was turned away by a priest from listening to Bhagabata interpretation (as it was in Sanskrit) and it is this incident that prompted him to rewrite in Odia. That itself was a major statement on identity assertion.

Rise of Odia pride, as the word means today happened during the reign of this dynasty. One of the most familiar stories of Odia identity is the conquest of Kanchi by Kapilendra Deva’s son, Purushottam Deva, where the narrative is that Lord Jagannath and his brother Lord Balabhadra fought alongside the Odisha army, strongly associating Lord Jagannath with Odias.

This projection of Lord Jagannath as a symbol of Odia identity has withstood the test of time. In the early 20th century, Maddhusudan Das, an Odia nationalist and a skilful lawyer—himself a Christian—argued unequivocally that Lord Jagannath can be the symbol of Odia unity and identity. Kotie Odia Gotie Kantharae Daka Trahi Jagannath (A crore Odias, appeal in one voice, save us O Lord Jagannath) was his appeal to the Odias. Das is regarded as the principal architect of formation of a separate state of Odisha—the first Indian state to be carved on a linguistic basis.

But before that—in the 1870s—there arose a situation where Odias had to fight to save their language. A Bengali school teacher posted in Odisha argued in a published pamphlet that Odia was not a separate language but an offshoot of Bengali. This was a direct assault on the identity of a language which has now been established as the oldest still-in-use Indo-European language. Odias, though angered, could not do much as a community for defending the language and it was the research of a British civil servant, John Beames, which established that Odia was not just a separate language, it was far older than Bangla! That was a major event in associating the language with the identity—something similar to the Rasagola debate, the only difference being that the Odias today are capable of speaking for themselves.

In recent years, establishing the uniqueness of Odia art, tradition, and practices—compared to other similar established forms in India—have become the most important effort in the direction of ‘building’ a strong identity. In the 50s, thanks to the efforts of Kavichandra Kalicharan Patnaik, a multi-faceted person who was a playwright, poet, researcher, composer, and theatre personality, Odissi dance was recognized as a classical dance. The efforts are still on to have the same tag for Odissi music. Meanwhile, in 2014, Odia got the classical language tag. It was the first spoken Indo-European language to get the status. That has resulted in a sort of renaissance and suddenly, the new generation seem to be taking interest in the language and culture of Odisha.

It is precisely this new generation—ably supported by a few tech-savvy users knowledgeable about various aspects in the 35-55 age group who are helping them with information and guidance—that is leading the efforts of constructing a strong, positive and unique identity for Odia culture, language and traditions leveraging social media, especially in the open platform, Twitter.

Whether it is convincing the world that Kharabela was the greatest ruler India has seen or Rasagola has originated in Odisha, or letting the them know that a festival like Raja that celebrates motherhood, more specifically the menstrual period of mother earth, has been celebrated in Odisha for centuries, this community of Odia Twitter users have continuously tried to assert the Odia identity, making people outside the state appreciate many unknown aspects of Odisha by celebrating them.

Between 2015 to today, these Odia Twitter users have managed to organically (just by cooperating with each other) trend more than 50 hashtags (some repeatedly every year) such as #Nabakalebara, #RathaJatra, #PakhalaDibasa, #RasagolaDibasa, #BhimaBhoi, #KhokaBhai, #Utkalmani #NuakhaiJuhar, #BaliJatra #Konark, #PrachiValley, #KharabelaTheGreat, #Pattachitra, #RajaParba, IncredibleChilika, #UtkalaDibasa, #OdissMusic and many more.

The new media plays a significant role in our lives and a lot of our habits, lifestyles, opinions and ideas get shaped on it. But unlike the traditional media, it is participatory and hence users are as much as ‘the influencers’ as they are ‘the influenced’.

Used well, the new interactive media platforms can be an effective medium for Odias to correct some historical mistakes and injustices committed against them.