The 70s and 80s Calcutta was where the action was. Naxalbari exploding across the state, Siddhartha Shankar Ray hogging headlines dealing with extremism and devising Emergency, Bengal at national centrestage. And then there was Satyajit Ray holding fort as the emperor of never-failing high quality global cinema.

Satyajit Ray was almost there, a few hundred kilometres away from Cuttack in Calcutta, but was eons away in brilliance. I consumed whatever I could on him – from newspapers, magazines (Illustrated Weekly, Sunday), books from AH Wheeler & Co at Cuttack station.

For me he was himself a hero, a creative storehouse who could do anything. He was a filmmaker, a graphic artist, a composer, typeface designer, sets designer. My father had met him, and his impressions influenced my thinking a lot.

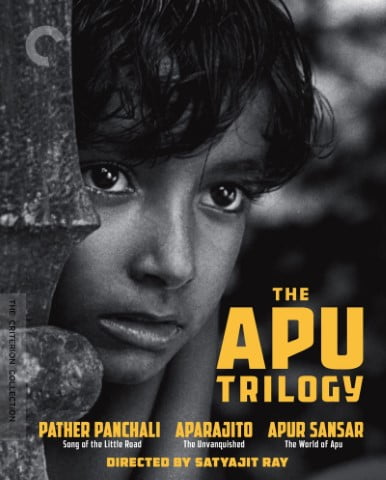

The story of financing the Apu trilogy with active support from Bengal CM Dr BC Roy gives me goosebumps even today. He went prepared with scene-by-scene sketches of the film, all his own doing. He was meant to conquer the world of cinema. Consumed in his art, a no-nonsense approach to work was quite an aberration because we always thought that creativity brings out a certain maverick streak in people and they veer towards alcohol or promiscuity quite easily.

Satyajit, who would have turned 100 on May 2, was without any distraction – he had no time to philander or lose his way. He was meant for the stratosphere.

If one debuts in virtually all departments of film-making in Pather Panchali, one can imagine his complete immersion in imagining, executing and finishing the film. Satyajit — moving up his benchmarks, exceeding expectations with every release and stirring the cognoscenti — was the creator and ambassador of higher culture and aesthetics like no one.

Cults like him lay cultures, not trends, or waves. He is eternal because his film-making was fluid carving, every scene pre-sketched, pre-imagined, soaked in the story so deeply that even then the scenes did not look as esoteric or alienated from reality. Realism on screen was real, the romance was not celebrating our poverty but a slice of life happening out there. Transported to the magical, lyrical silver screen.

This is the uniqueness of Satyajit – he himself breathed every inch of his screen, camera and characters. This gave him the supreme confidence and often he was a quiet person. Had to be. When you are so touched by every moment, there is nothing to speak. His films often spoke in quiet scenes.

What mesmerised me was his economy of expression. He was so detailed that he could capture it minimally. No filmmaker understood the way he did that cinema is a visual medium first and then verbal, and that no words need be said. Of course, this holds sway if the films are like his poetry on screen. In Aranyer Din Ratri, the forest becomes a leveller for the apathy of city slicker. Today, as talk on forests is raging, the film is a good reminder of the possibilities of film-led societal change. I consider Aranyer Din Ratri — including its music and characterisation of Soumitra Chatterjee, Sharmila Tagore and Rabi Ghosh — much ahead of its times. The dilemma in Jaya’s character is so well portrayed with sharp, crisp dialogues.

Satyajit was the master of everything – unbelievably rare. Being a skilled calligrapher, an adman and a music composer, his scene compositions were splendid and futuristic. Charulata was his personal favourite, probably because it was a perfect movie. Visualization, measured expressions, amazingly touching aesthetics, it satiated the Master who was always a perfectionist.

I haven’t watched many of his documentaries and shorts, and that’s what I want to complete at the earliest. But with his films, his persona, his beliefs, his communication, his finding poetry in the midst of an underdeveloped economy, his discipline as a filmmaker, his pragmatism, astuteness as the culture-setter — Satyajit comes once in a long time. Rest of the times, let’s soak in his craft and get inspired.

Ray exemplified the dexterity and confidence of making world-class cinema with highly-rationed budget but maximum output. The master perfected ‘maximum bang for the buck’ like no one else. Probably he was the only ‘regional’ filmmaker in the world whose films were global. Satyajit Ray taught us the glory of celebrating cinema in totality, without ever being constricted to the ‘regional’ tag.

For him the budget didn’t matter, nor did the language or the genre. What only mattered was the final quality of the story, the narration, the plot, the nuances, the music and the overall cinematic oeuvre. No doubt he was an auteur and maybe the best in one hemisphere.

He was very cosmopolitan – he knew all about the art powerhouses of the world. His exposure gave him the world view and world acclaim, too. His art on celluloid segregates cinema into two periods – before Satyajit and after Satyajit. Mumbai mainstream Bollywood, strong regional film hubs like Kerala, Bengal flinched while facing the towering radiance of brilliance & finesse.

Manik da sitting in Calcutta could make the world stand in ovation. Not many ‘regional’ filmmakers could cross the borders and look at the big blue sky – like Apu and Aparna do even in the physical limitations of a tiny room overlooking a railway yard in newly-inhabited Calcutta city. Ray could have never been contained within the local/regional framework. He had to outgrow it and he did it on his debut.

Again, he must be the first in the world to have taken this kind of a high leap in the first jump itself. Quality is irrepressible, indomitable. Who cares about regionalism? His art was limitless.

Somewhere he knew that he was extraordinary and that’s the reason probably why he was not very much available in social soirees or huddles. He was a cut much above the rest and was always in the background as the master churning out his masterpieces. He was absent but was never absent. Never is absent too.

Satyajit Ray was a star next door, but high above in the skies, glittering for the whole world. You have to extricate yourself from the mediocrity to reach the skies, to him.