Towards A ‘Science’ Of Translation In Odisha

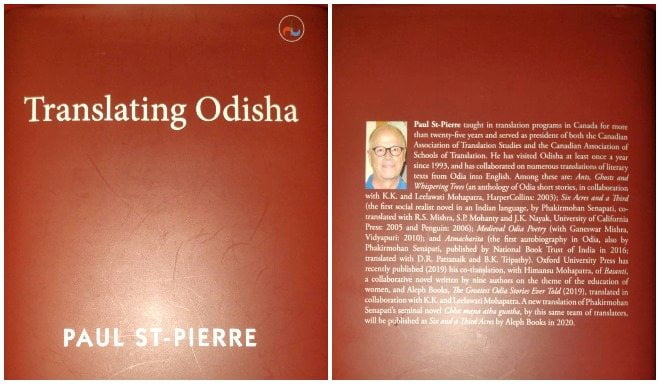

Review of Translating Odisha by Paul St-Pierre. Bhubaneswar: Dhauli Press, 2019. Pp. 436. Rs. 995.

Preamble

I am thinking back to the year 1997, which will explain the genesis of this book and the fact of it being inscribed to the memory of Ganeswar Mishra.

Three or four years before this watershed year, Mishra had started Sateertha, a cultural organization that doubled as a small publishing venture. The aim was to promote Odia literature through translation, criticism and bibliographic compilations of works done in offbeat areas such as autobiography, travel writing, diasporic writing with a link to Odisha and the like. In 1997 Sateertha aimed even higher, moving from the magazine format to book format and conceiving of a special volume on Odia Women’s Writing in English translation. The volume, co-edited by Mishra and Paul St-Pierre, saw the light of day at the end of the year.

This publication marked the official entrance of St-Pierre into the translation scene in Odisha, and, specifically into the scene of Odia Literature in English Translation (OLET). True, he was yet to get the official tag of translator, or, co-translator, strictly speaking. That would happen two years down the line, in 1999, with the appearance from Sateertha of The Holy Man: A Play, an English translation of the first Odia play Babaji Nataka by Jagan Mohan Lala. St-Pierre would be listed here as a co-translator with Mishra. The rest, as they say, is history. In the next seventeen years the number of translated works (done by several hands) involving St-Pierre as a collaborator would rise to a staggering forty four. The list given at the end of Translating Odisha says it all. It is a prodigious haul, for sure, and culturally symptomatic too, as numbers in this book usually are. St-Pierre has a way of making numbers, figures, statistics and data speak eloquently.

From Translator to Translatologist

Which brings me to my main point. It is not so much St-Pierre the translator as St-Pierre the translatogist – he was Professor of Translation at Montreal University – that one meets with in this book. Now what is the difference between the two? A translator is someone who – and I would prefer to quote St-Pierre here – ‘represents’ a text in one language and ‘re-presents’ it in a new language’ (p. 81). A translatolgist is, in turn, someone who takes translations as objects of scholarly investigation. He is interested in how in cross-over situations they mediate power relationships as they negotiate cultural difference. What a translatogist does, therefore, falls into the sphere of Translation Studies (also called the ‘Translative Turn’), an interdisciplinary approach drawing on history, critical theory, linguistics and area studies. This is what defines Translating Odisha, as the opening essay of the book “The Beginnings of Translation Studies” succinctly delineates. That the book is a work of ‘translation studies’ may disappoint some enthusiasts of translation in and outside Odisha who believe simply in doing the job, not in talking about it. But for those of us who are of an Oscar Wildean persuasion and accept that talking about a thing is more difficult and challenging than doing it, Translating Odisha is absolutely riveting.

From English to Odia

There is, however, another surprise in store for the readers of Translating Odisha. Contrary to what we may conclude from St-Pierre’s chosen area of operation, it is not translating towards English, but towards Odia, that constitutes the centrepiece of the book. I say this despite two whole sections in the book (accounting for 10 out of 22 chapters if one leaves aside the 15 occasional pieces) devoted to Phakirmohan Senapati and Jagannath Prasad Das, the two Odia authors St-Pierre has been majorly invested in. But even here St-Pierre is concerned less with the ‘how-to’ of translations than with the specific selections and ‘partial perceptions’ (p. 12) they embody. So the book is about the whys and wherefores of translations into Odia, which is the normal practice of translation, though not necessarily a normative one in a linguistically diverse country like India. In chapter after chapter he delves into his painstakingly assembled bibliography or database, as he calls it, of around 5650 – the number has now risen to 6000 – translations into Odia produced between 1807 and 2004, trying to milk the data for what it is worth.

The four-phase breakdown he offers invites us to see Odisha evolving from a colonial society (1807-1866) that robbed it of its identity to a postcolonial one, conscious of its identity as well as of its place in India and the world. Three distinct phases of the postcolonial are then identified: a nativist, inward looking phase (1867-1941), an internationalizing one in the wake of India gaining Independence (1942-1973), and, finally, during 1974-2004, a cross-regional phase reflecting Odisha’s place in the federal structure of India’s polity. The phase of globalization that gathers pace after 2004 is probably to be best read off from the translations of Odia literature into English in which St-Pierre has participated. But this is told only in passing, especially in the chapter “Challenges for Translation in an Era of Globalization.”

Science of Translation

In this disclosure of the shifting social, historical and cultural trends of Odisha through the prism of translational choices of individuals and groups St-Pierre has taken translation as near as possible to being a science. The reason why I say science is because of a simple thesis that St-Pierre reiterates and demonstrates throughout his book. The thesis is this: translations are produced less due to the subjective choices of individual translators than to the objective forces acting through the individuals. It is true, though, that these forces and the route to their internalisation can only become evident in retrospect.

I find myself both agreeing and disagreeing with this thesis. Disagreeing, because in case of our joint translation of the Odia novel Basanti (published as Basanti: Writing the New Woman from OUP in 2019) the act certainly originated from a strong individual passion to rescue from oblivion this unique feminist work written collaboratively. Agreeing, because the contemporary interest in archiving works that are outside the mainstream meant that two current trends tended to converge around this work. The same is true of our translation – recently accepted at Penguin – of the off-centre modern Odia novel Nija Nija Panipatha (Battles of Our Own) by Jagadish Mohanty. To quote a favourite saying of St-Pierre, translations ‘betray’ not in the sense of unfaithfulness to an original text but in the sense of overtures beyond the immediate context.

Conclusion

Translating Odisha is packed with information and insights relating to translation, to how it is practiced in Odisha and with what tools. It brings out both the strength and value of translation and the richness of Odisha as a field of cultural transactions in a dazzling display of Translation Studies in action. Translators can now go about their tasks with renewed confidence and vigour. That is because a translatologist has cleared the decks by boldly reversing ‘the devalued paradigm of reflection, refraction, and reiteration’ (p. 199) within which translation has been contained.

Manu Dash of Dhauli Press has done a commendable job with book production, delivering the book in a hard cover of Spartan simplicity and elegance.

Comments are closed.