Ram and Ravana, the synonyms for good and evil respectively in the Hindu world, have travelled together for millennia, rendered inseparable by virtue of their linked destiny.

But Ram was more than just a prince of Ayodhya who straddled the subcontinent to rescue his wife Sita from the clutches of the abductor, Ravana, the king of Lanka. Ravana, similarly, was more than just the personification of evil that Hindus evoke him as.

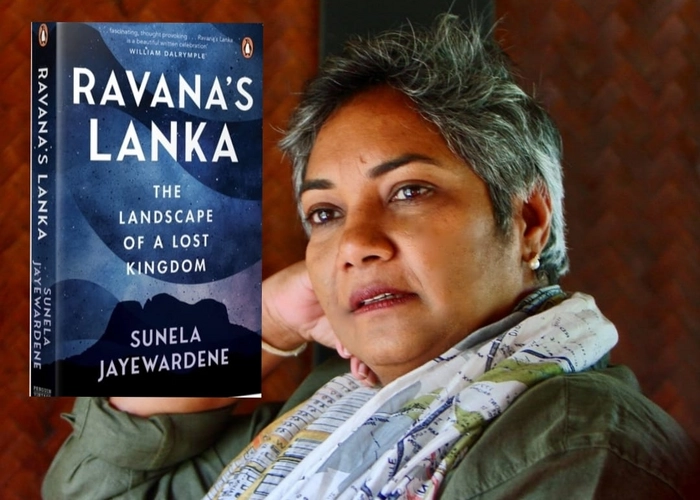

A recent book, Ravana’s Lanka: The Landscape of a Lost Kingdom (Vintage/Penguin Random House, Rs 499), goes beyond this sutured identity of the most well-known ruler of Lanka and cleaves it off the joint that binds it to Ram’s identity, to focus solely on his historical antecedents. The greatest of the Mayuranga kings, Ravana ruled before the officially accepted starting point of Lankan history, the arrival of Prince Vijaya from Magadha in India, who inaugurated the Vijayan dynasty in 543 BCE. This dynasty lasted a thousand years, and the subsequent waves of rulers, including the very latest European colonisers, only pushed Ravana’s story into obscurity.

The author of the book, Sunela Jayewardene, one of Sri Lanka’s most renowned environmental architects, undertook travels across the island nation to remove layers and layers of dust on the historical truth of Ravana, which survives in folklores in remote villages of the tropical forests. She speaks at length about her discovery of the story of Ravana in an interview with Archana Khare-Ghose. Excerpts

Q1. Even in India where Ravana’s effigy is burnt every Dusshera in a symbolism of the victory of good over evil, it is an unequivocally accepted fact that there was no bigger devotee of Lord Shiva than Ravana, and that there was no bigger learned Hindu than Ravana. Yet so little is known about his historical times. Why do you think that is the case?

I think that despite his devotion to Lord Shiva and all the good he may have done for his people, ultimately, he was the loser. The winner’s narrative always supersedes — that it seems, is a core characteristic of human nature, unchanged despite the millennia, civilizations and technologies since. The Lanka that was left behind by Lord Rama’s triumphant army, was probably too broken to compile a cohesive story… This was followed by the arrival of Prince Vijaya and the building of a Sinhala race, then the European colonisation and each with their own narrative. Perhaps there never was time for recovery and reflection on the kingdom of the Yaka!

Q2. When did you first get fascinated with the story of Ravana and the need to bring it out of the cobwebs to make it as much a part of living history of Sri Lanka as history from the arrival of Vijaya, and post-Vijaya’s arrival?

My deeper interest is actually in the kingdom that Ravana and his dynasty ruled over. This interest began after my husband and I purchased a property in the remote central forests of Sri Lanka. As I started spending more time here and hearing the stories of the people of the rarely frequented hill villages, their conviction and their ability to tie their tales to specific landscapes, drew me in. I feel this is a facet of Sri Lankan history that needs airing… a story that needs to reach beyond the tiny hamlets they’ve been lodged in for all these millennia.

Q3. Why do you think Sri Lanka’s historians and archaeologists haven’t paid as much attention to Ravana’s times as they should have?

Perhaps, it is because there is still so much that is relatively recent and untouched. Perhaps it is because passion and pride in their work seems to have evaded government archaeologists. In addition, rocking the boat of the accepted narrative of Lanka, the story written in the Mahavamsa (the chronicle that begins in 500 BCE), would be problematic on many fronts.

Q4. Reading the book gives a wholesome idea of the challenges you have faced in this unique journey of yours. Could you share which was the biggest challenge of them all, and how did you tackle it?

My challenge has always been time — there’s never enough time for me to explore all that interests me. I have now retired from my profession as an environmental architect, but still, I find it’s time that I never seem to have enough of; days to trek through forests, travel to meet people who still keep ancient secrets, make a date with some rare ritual… time to spend in search of forgotten histories.

Q5. Do you think reclaiming a glorious, yet disregarded ancient history of the island nation can help heal some fault lines that have divided the people of Sri Lanka in recent history, of which the bloody civil war was a painful chapter?

Yes, I certainly do! If the history of the foundation of our people, the three ancient races that coexisted and intermarried, becomes a more accepted narrative — even an official narrative — then our commonalities will override our differences and it will be easier to seal the cracks.

Q6. Your 2020 book, The Line of Lanka, is described as an unprecedented lens on the nature and culture of Sri Lanka. Is there any other subject on Sri Lanka that you hope to write on in future?

No! I’m still getting my head around changing gears from architect to author. There is so much to write about but I have not focused on anything as yet.

Q7. How much has your life as an architect influenced your career as a writer who is trying to train a hitherto untried viewpoint on the unknown history of the island nation?

I think it has been very influential. It is the technological advances that are so evident to a trained eye, that fascinate me the most. I see forms and applications of seemingly simple but actually very sophisticated engineering and irrigation systems that I think I would have missed and failed to understand, if I was not an architect. It is this understanding that has convinced me of a forgotten superior civilization and I write quite extensively on these subjects in both my books.

——–The interviewer is an Art critic, Curator, Journalist and Blogger.

(By Arrangements With Perspective Bytes)