The Odisha government has recently announced what it calls the Manoj Das International Literary Award in the memory of Odia writer Manoj Das who passed away last month. The award, carrying a cash prize of Rs 10 lakh, will be conferred annually on writers from Odisha for their creative contribution to English literature.

This has led some to question if it was a good idea to restrict the award to people from Odisha. While many fans of Das — arguably the most popular writer among this generation of Odia readers — think a pan-Indian award would have done more justice to his memory, others think the award to Odia writers could encourage more Odias to write in English — thus opening Odisha to the world, which would be the right tribute to the legendary writer.

Both the arguments have their own merit. I would go more with the second logic, because awards by state bodies in the name of luminaries often do not get well acknowledged, let alone getting visibility. The Lata Mangeshkar Samman of Madhya Pradesh government and the Akshaya Samman given by Akshaya Mohanty Foundation are just two examples. The Foundation has conferred its Akshaya Samman on the likes of Manna Dey, Ilaiyaraaja and Asha Bhosle. But to what effect? Do these awards even get mentioned when these artistes are written or spoken about?

But there are those who question the current announcement. They ask how many Odias actually write in English. They argue the number is so small— especially if you consider prose— that it is difficult to expect an award to change it overnight.

That also is a valid point.

At this point of time, it is not known if a translation in English would qualify for the award or not. But if it does, I think it will achieve its objective very well.

This is why.

While it is difficult to expect people to suddenly start writing afresh about Odisha in English, there is a vast treasurehouse of Odia literature that is waiting to be translated. These works have withstood the test of time for their effective portrayal of the culture, values and lifestyle of Odisha. And a good translation can do wonders to introduce these to a wider audience.

This is especially true in case of novels whose broad canvases give enough scope to writers to paint settings, lifestyles and times realistically and vividly. Just think about “Chha Mana Atha Guntha” and its realistic depiction of Zamindari exploitation as well as of the colonial values making inroads into Odisha. Or about “Matira Manisha” – how well it portrays Odia village life! Likewise, “Paraja’ is unforgettable as a saga of tribal life. Or “Desha Kala Patra” and the way it gives us insights into Na’anka famine and early Odia nationalism.

A lot remains to be done, though.

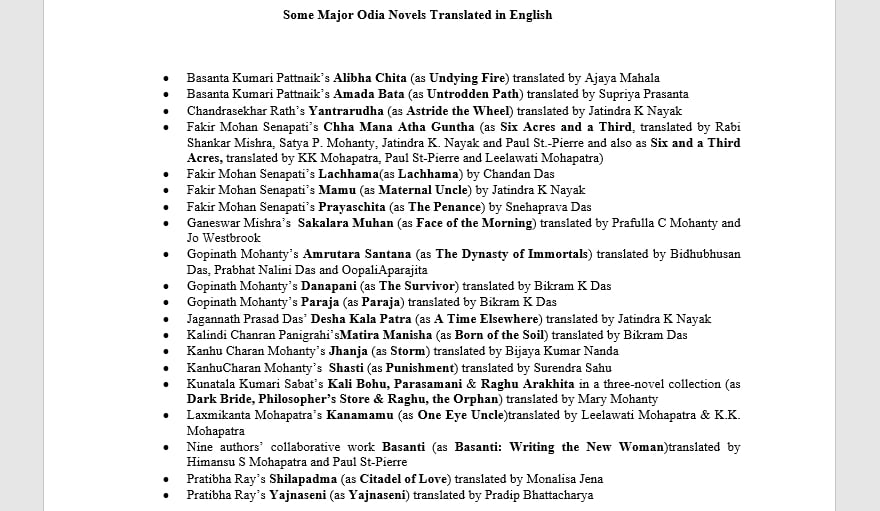

While the efforts by Sahitya Akademi and individuals have resulted in translation of many Odia short stories into English, published as anthologies of Odia stories, or of individual authors and also as part of anthologies of English translations of Indian language stories, the number of novels that have been translated is still not sizeable.

Many good Odia novels remain to be translated. Also, after the publication of the English translation of the first Odia dalit novel, “Bheda” by Akil Naik, and of the first feminist collaborative novel “Basanti” by Oxford University Press in 2017 and 2019 respectively, there is raised expectations about other subaltern and non-mainstream novels from Odisha.

The number of good translators is small. Some established names in this field are Bikram Kishore Das, Jatindra Kumar Nayak, Kamala Kanta Mohapatra & Leelawati Mohapatra. The field is of course widening thanks to contributions from some notable names like Snehaprava Das, Monalisa Jena, Mary Mohanty, Bijay Kumar Nanda and Supriya Prasanta. Considering that some others such as Lipipuspa Nayak, Basant Kumar Tripathy, Dipti Ranjan Pattanaik, Rabindra Kumar Swain, Askok Kumar Mohanty, Raj Kumar, Chandan Das (late lamented), Himansu S. Mohapatra and Malabika Patel are into active translation of other forms of Odia prose to English means, there is a lot of hope for translating novels.

Paul St-Pierre is an important name to be reckoned with in the field of Odia Literature in English Translation. It must be underlined that he translates in collaboration with translators whose first language is Odia. Some acclaimed titles of translated fiction that he has been collaboratively involved with are “Six Acres and a Third” (2005), “Six and a Third Acres” (2021), “Basanti” (2019), “Lacchama” (2020) and “Letters to Jorina” (2021). He is, in addition, a historian and critic of translation who has published a well-researched database of works translated into Odia from 1807 to 2006 in his book “Translating Odisha” (2020).

Any investment – an award is just one of the ways – in encouraging translation from Odia to English is an investment in promoting Odia culture across the globe. It would not just dispel ignorance and misconceptions about Odisha and Odias; it would help open up Odisha to the world. That is extremely important for enhancing our soft power, which seems to be a priority for this government. Translation of prose fiction with ample narratives is one of the best messengers of our values and culture.

If the award in the memory of Manoj Das can include translations, it will be a service to Odia literature besides being an incentive for translations from Odia to English.