With Khurda of late reporting the highest number of COVID-19 positive cases in Odisha on Saturday, I began thinking of writer Daniel Defoe’s quote: “Fear of danger is ten thousand times more terrifying than danger itself.” We are all living in fear. As the pandemic-induced restrictions on our subconscious and bodies have unleashed a New Normal, my mind wandered off to Defoe’s famous literary character Robinson Crusoe. Like Crusoe, we want to escape. Like Crusoe, we are attracted towards the unknown lands – an insatiable dying quest for travel that emerges from months of confinement in our homes.

Defoe was born in 1660. Though the exact date of his birth is unknown, some assume it to be September 13. Published in 1719 in London, the novel ‘Robinson Crusoe’ pioneered the genre of realistic fiction. The popular premise holds that it is based on the adventures of a Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who was marooned in an island in the Pacific for about 5 years (1704- 1709). However, Defoe extends the timeline to 28 years in his novel.

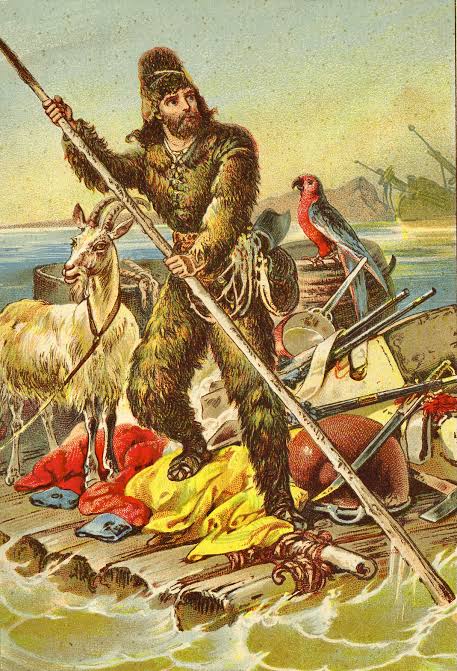

Crusoe’s first voyage to Guinea puts him in great peril. He somehow escapes from the jaws of death. But that does not stop him from going for trade to Africa where pirates capture and enslave him. He somehow escapes and goes to Brazil where he becomes the owner of a plantation. Then follow his adventures on an island.

Today, because of the popularity of the character, Crusoe has become a lingo in the dictionary. It stands for “a solitary castaway: one who lives or survives by his or her own unaided effort and ingenuity” (Merriam-Webster). Its adjective is Crusonian. Many literary genres have developed out of the name of the novel: ‘Robinsonade’, ‘Robinsonade proper’, ‘Science fiction Robinsonade’, ‘Apocalyptic Fantasy Robinsonade’, and ‘Inverted Crusoeism’. ‘Robinsonade’ refers to a literary genre that deals with the story of a protagonist usually marooned or castaway on a secluded place/ island. The term was coined by Johann Gottfried Schnabel after the novel Robinson Crusoe. In addition, ‘Robinsonade Proper’ includes technology, nature, economy and civilisation. ‘Science fiction Robinsonade’ is scientific literature in which people arrive in an uninhabited land and build a settlement. The examples: John W Campbell Jr’s ‘The Moon is Hell’ and Tom Godwin’s ‘Survivors’. ‘Inverted Crusoeism’, coined by J G Ballad, means deliberately ‘marooning’ oneself for spiritual introspection.

There are at least 52 literary adaptations of the novel Robinson Crusoe and 21 other adaptations including TV series, films, video games and web comics. Perhaps, the first film on Robinson Crusoe titled by the same name was a silent one released in 1927. Thinking about the film adaptations, what impressively springs up in the mind is Tom Hanks’ role in ‘Cast Away’ (directed by Robert Zemeckis and released in 2000) rather than the 1997 American film ‘Robinson Crusoe’ starring Pierce Brosnan. The Brosnan-starrer did not gain much critical acclaim; rather ‘Cast Away’ struck us in the right moments although it wasn’t a direct/ faithful adaptation. However, Brosnan with his long hair and unkempt beard had a compelling screen presence akin to the protagonist. There have also been at least 12 other films made on the book. Popular TV adaptations include ‘Expedition Robinson’ and ‘Survivor’. Many stage adaptations – famous ones directed by Isaac Pocock, Jim Helsinger, Steve Shaw and Jacques Offenbach – have appeared. Comic illustrations and animated cartoons have also been published in 1943, 1957 and 1988. Walt Disney tried to give an interesting twist to the story by making a film that has a lady in place of the character of Man Friday (who Crusoe befriended on the island); she is called ‘Wednesday’. Man Friday has also found a place in the dictionary.

Crusoe reminds me of Tennyson’s Ulysses: the same undying quest for adventure and a daring spirit to face the unknown odds. Both get uncomfortable in the comforts of their home. To quote Ulysses:

“I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy’d

Greatly, have suffer’d greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro’ scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour’d of them all;”

Crusoe differs from Ulysses in one aspect: he is materialistic. The limitless greed to amass endless wealth and luxuries drives Crusoe into lonely islands and unknown terrains, whereas Ulysses is a wandering spirit whose lust for adventure is primarily his love for travel to see new cities and meet new people and have new experiences. Ulysses follows “knowledge like a sinking star” and Crusoe keeps on acquiring wealth to satiate his unsinkable rapacity.