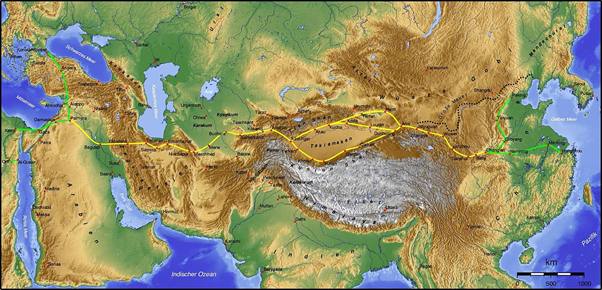

It was a balmy day on March 2, 2001, following the melting of the snow, in the picturesque Bamiyan Valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan that years ago had seen the laden hoof-trails of highly valued silk merchandise, led by a people from the faraway lands of Xinjiang, China. The route was recognized and acknowledged as The Silk Road, which was a network of trade routes which connected the East and West; and was central to the economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between these regions from the 2nd century BCE to the 18th century. The day was set to significantly alter the course of mankind’s cultural history, as we will see in the succeeding paragraphs.

The picturesque valley was the site of several Buddhist monasteries, and a thriving centre for religion, philosophy, and art. Monks at the monasteries lived as hermits in small caves carved into the side of the Bamiyan cliffs. Bamiyan shared the culture of Gandhara, whose existence is attested since the time of the Rig Veda (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BC), as well as the Zoroastrian Avesta; as the sixth most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda. Gandhara was one of the sixteen mahajanapadas (large conglomerations of urban and rural areas) of ancient India mentioned in Buddhist sources such as Anguttara Nikaya (Higham, Charles,2014, Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations, Infobase Publishing, pp. 209).

In the epochal history of mankind, there could not be a better example of cultural diversity that saw the intermingling of people, values, beliefs, language, economies, religion, arts and literature.

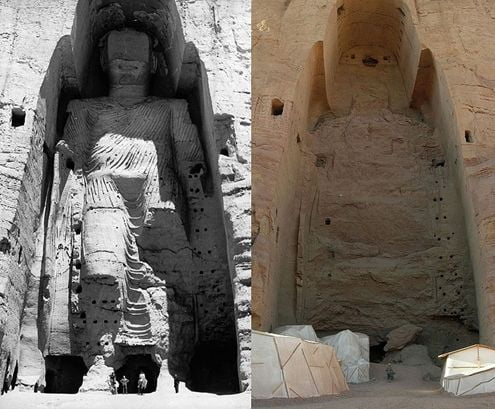

The times that went by saw the Silk Road expand and the Bamiyan valley witnessed the advent of many empires, kingdoms and confluences of varied cultures, religions and people that influenced and controlled the valley and the surrounding areas. Bamiyan and its contiguous areas represented the quintessence of the coming together of cultures in its myriad diversity; until the Taliban emerged in 1994 as one of the prominent factions in the Afghan Civil War and took control of Afghanistan. They were soon set to change the course of Bamiyan valley’s history for ever with their strict code of Shariat law that abhorred the worship of idols; including the imposing figures of Buddha (built in 507-554 CE, in the classical blend of the Gandhara art), who looked down reverently at the passing admirers since the beginning of Gandhara days, carved into the rock face of the Bamiyan mountains, a World Heritage Site.

That balmy day of March 2, 2001 watched in silence as the uncompromising Taliban marauders, who over several weeks, dynamited the venerated statues and destroyed them while the world watched aghast in a muted protest. The Bamiyan symbol of cultural diversity was desecrated beyond repair.

In the aftermath of the shocking and deplorable destructive event of Bamiyan and subsequent overthrow of the Taliban regime, the world led by UNESCO/ UNO took the constructive decision, after due deliberations, in 2001 and declared 21 May as the World Day of Cultural Diversity. The day provides us with an opportunity to deepen our understanding of the values of cultural diversity and to advance the four goals of the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions adopted on October 20, 2005:

- Support sustainable systems of governance for culture

- Achieve a balanced flow of cultural goods and services and increase mobility of artists and cultural professionals

- Integrate culture in sustainable development frameworks

- Promote human rights and fundamental freedoms

“Culture is an integrated system of learned behavior patterns that are characteristic of the members of any given society. Culture is the total way of life of particular groups of people. It includes everything that a group of people thinks, says, does and makes its systems, attitudes and feelings. Culture is learned and transmitted from generation to generation,” said Robert Kohl, the renowned sociologist. Culture is the arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively. It consists of the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society. Culture is a word for the ‘way of life’.

In addition to its intrinsic value, culture provides important social and economic benefits. With improved learning and health, increased tolerance, and opportunities to come together with others, culture enhances our quality of life and increases overall wellbeing for both individuals and communities.

Every country, every community are strongly tied together by an intricate tapestry of individual values, norms and a specific history, to understand their culture is to understand them. Culture and its impact on the communities it was born of, is a beautiful, multifaceted entity which gives strength, identity and purpose to its people.

“A nation’s culture resides in the hearts and in the soul of its people.” – Mahatma Gandhi

Why does cultural diversity matter

The lessons of history tell us that three-quarters of the world’s major conflicts have a cultural dimension. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability and development.

Cultural diversity is a driving force of development, not only with respect to economic growth, but also as a means of leading a more fulfilling intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual life. This is captured in the various coming together of people in cross-cultural get-togethers, which provide a substantial basis for the promotion of cultural diversity. Cultural diversity is thus an asset that is indispensable for human understanding, poverty reduction and the achievement of sustainable development.

At the same time, acceptance and recognition of cultural diversity, in particular through innovative use of media and Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) are conducive to dialogue among civilizations and cultures, respect and mutual understanding.

Indian culture in context

India’s variegated culture offers astounding variety in virtually every aspect of our social life. The diversities of ethnic, linguistic, regional, economic, religious, class and caste groups abound the Indian society, which is also permeated with immense urban-rural differences and gender distinctions. Differences between north India and south India are particularly significant, especially in systems of kinship and marriage. Occupying an area as varied as Europe, India is more in cohesion than any other single nation-state. Indian society is multifaceted to an extent perhaps unknown in any other of the world’s great civilizations. Adding further variety to contemporary Indian culture are rapidly occurring changes affecting various regions and socio-economic groups in disparate ways. Yet, amid the complexities of Indian life, widely accepted cultural themes enhance social harmony and order.

Impact of COVID-19 on the cultural sector

The illusive virus has brought a plethora of damages in its wake: cultural events cancelled, cultural institutions closed, community cultural practices suspended, empty UNESCO World Heritage sites, heightened risk of looting of cultural sites and poaching at natural sites, artists unable to make ends meet and the cultural tourism sector immensely affected. The impact of COVID-19 on the cultural sector is being felt around the world. This impact is social, economic and political: it affects the fundamental right of access to culture, the social rights of artists and creative professionals, and the protection of a diversity of cultural expressions.

The unfolding crisis risks deepening inequalities and rendering communities vulnerable. In addition, the creative and cultural industries that contribute 3% to the total combined global economy and account for 29.5 million jobs worldwide, is indeed disastrous (source: “UNESCO Paper on Culture & COVID-19: Impact and Response Tracker – Issue 2”).

In more ways than one, the people of the world are at a crossroads today. The world societies with their unique cultures are beset with a dilemma of being ‘nowhere’; especially in the aftermath of the coronavirus. There are new alignments with billions of people in the crosshairs of uncertainty and delusion; a case in point is the state of the migrant labourers in India. The migrant laborers are among the most vulnerable part of the ‘informal sector’, which make up 80 per cent of the country’s workforce. The Union government’s 2017 economic survey said, “If the share of migrants in the workforce is estimated to be even 20 per cent, the size of the migrant workforce can be estimated to be over 100 million.” Consider the mental innards of these hapless people in desperation to return to the closet of their cultural identities. It is not just them; even the rest of us who remain bound with our own cultural vulnerabilities that we seem to covet under disguise. Time has come for all of us to return to our common cultural sphere unique with its Indianness and proclaim to the world at large: “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (the world is one family)” and let it resonate in the not so far away blessed Bamiyan valley.