I joined the erstwhile Ravenshaw College in 1958 and stayed in East Hostel. Room number 36, a large lecture hall, was close to the hostel. The loud and smart footsteps of a newly-recruited lecturer used to resonate regularly in the long corridor leading to room number 36, where he would teach students of political science. The young man walked like a General, with great confidence and aplomb. There was something in him that caught my fancy. I was inquisitive and learnt more about him. He was Mr R N Das, who had passed out from Patna University and joined Ravenshaw College. I was then a student of science; but unwittingly, started seeing merit in studying humanities, preferably, political science.

He joined the IAS in 1959 and served as sub-divisional officer in Bargarh while my father was Deputy Commissioner in Sambalpur.

In the early nineties I worked as Finance Secretary while Mr R N Das was Chief Secretary, and had the opportunity of observing him closely. It was a learning and enriching experience. One day Chief Minister Biju Patnaik called me to his chamber to assist him in sorting out an issue. On my enquiry about the nature of the issue so that I could have some time to think and offer him possible solutions, he said, rather vaguely, that it is related to the allocation of responsibilities to two senior officials. It had nothing to do with the affairs of the Finance Department of which I was in charge. The officers concerned were senior to me and I would not be comfortable at suggesting something over what the Chief Secretary could have been suggested on the issue. I, therefore, went to the Chief Minister a bit reluctantly but only after meeting Chief Secretary R N Das. I informed him about my task before the Chief Minister. Mr Das told me that while both the officers were competent, the humbler of the two shouldn’t feel that his capabilities have not been acknowledged. He was only pointing out to me the same golden principle of governance that my father had spoken years ago. “You are about to join the civil service,” my father had told me, “and you will have many occasions when you have to choose one out of two with equal merit. In such situations tilt the balance of justice in favour of the weaker.”

I met the Chief Minister; he had kept his aides away from the discussion. After talking to me, the Chief Minister took a decision on the issue.

Chief Secretary R N Das had sensitised me on yet another important principle, which helps in governance. He once told me that if an officer while examining an issue — say, granting of permission for construction of a building on a piece of swampy land — takes a stand that it cannot be granted in tune with the existing rules, then he should have the courage to stick to his stand even if he is pressurised by the highest authority to grant permission. If he succumbs to pressure and accords permission by giving a new interpretation to the rules, he should be viewed as an officer amenable to pressure. If he acted as he did under pressure; he could have acted that way independently as well at the beginning. In other words, he had advised me to have a broad mind, a positive and helpful attitude and not to be amenable to pressure.

As Chief Secretary, he preferred secretaries to act independently without breathing down their necks. Even in very important forums, he would let secretaries handle the situation rather than overshadowing them.

When the issue of drought and mass-scale deprivation in the KBK region of the state became acute, the government wanted to come up with a long-term action programme. It was also decided that a concept paper had to be prepared and presented to the Centre. He asked me to prepare it immediately. I started working on it. He would quietly enter my room to find me working on it and encourage me to complete the task on time. It was done and after the state government’s in-principle approval of the strategy outlined in the paper, we attended a meeting chaired by the Cabinet Secretary which was attended by a few secretaries to the Government of India as well. The Cabinet Secretary would listen to some participants and say he was unable to get a feel of Kalahandi. The Chief Secretary turned to me and I made an attempt. It worked. The meeting passed off well.

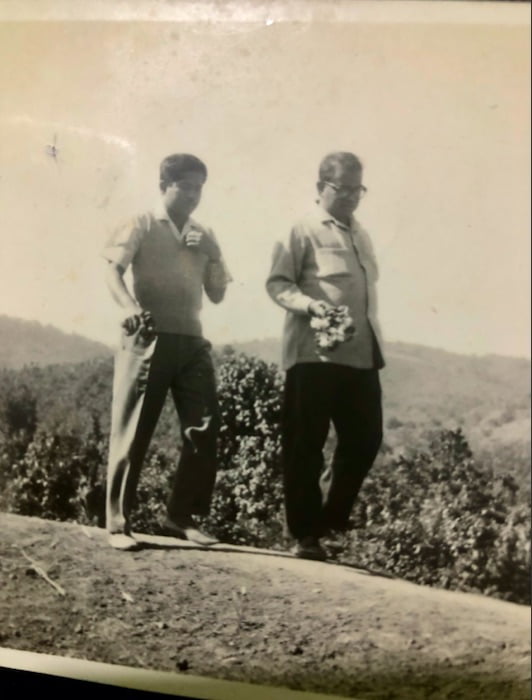

On one occasion, Mr Das was in Delhi while I too was in Odisha Bhavan. He suddenly asked me to accompany him to Patna. He was to discuss with Bihar officials on the Subarnarekha multi-purpose project. The meeting went off well with an assurance from Bihar that work within their state for which we had made payment would be expedited. The Chief Secretary then decided that we went on a drive towards Patna University. He looked at his alma mater with emotion. So did I, for that was the place where my father did his MA in Economics.

On another occasion, he asked me to accompany him to Puri to see the repair work in the Sanctum Sanctorum of the Jagannath Temple when the three deities were shifted to a temporary altar for the repair work to go on. We spent the night in the PWD Inspection Bungalow, newly constructed close to the beach and visited the temple the next morning to pray during mangal arati. It was a solemn experience.

One day both he and I were called by Chief Minister Biju Patnaik. We went to Naveen Nivas where a political meeting was on in a room on the first floor. We waited outside and the Chief Minister came out. His tone sounded defensive. He said he was aware of the state’s financial problem but there was a strong demand from political leaders of the party that the government should start paying unemployment allowance to people without jobs. The Chief Minister waited for our response. The Chief Secretary asked me to respond. I said it was just impossible. The Chief Minister was nice enough to say he knew that and went inside. We came down and the Chief Secretary looked at me with wide eyes and said, “Just imagine, what are they asking for !!”

A short mention needs to be made about that cruel day in 1993, the day of the hoodlums around the state Secretariat. They soon took over the Secretariat. The state’s Intelligence agency, it seemed, had no clue and the presence of policemen was perhaps limited to a couple of non-serious men in uniform lazing around. Nearly 100 hoodlums made forcible entry into the Chief Secretary’s office room. Those days, the room was too small even to accommodate 20 people. Mr Das was brutally assaulted, his office ransacked, furniture and equipment smashed. The hoodlums chose the time, both of entry and departure. The worst could have happened that day to a most worthy civil servant of the state. The Home Secretary had spent over an hour in a desperate state of fear and apprehension. I was Finance Secretary. The unavoidable austerity measures the government had given effect to were issued from the Finance Department. My staff had sensed the mood of the mob right. I could be the next target. I was whisked away into the room vacated by an Additional Secretary and kept in the perfect safety of the locked-up room. After sometime, the noise of the wild subsided and I pleaded to be allowed to go to the Chief Secretary. My staff turned down the plea. Through the window, I watched a few government vehicles being damaged. While that was bad enough, what made my head low in sheer shame and anger was the sight of about two sections of policemen running away as the hoodlums chased them. Finally, I came out of the room and went to see the Chief Secretary. I saw him in the office of the Chief Minister. There were bloodstains on his shirt. Our eyes met and this nobleman smiled at me and enquired if I was fine. I wiped my eyes and sat with him for some time till he was escorted back home. The next day, I found him perfectly normal and he told me that the Cabinet Secretary had called, wished him well and suggested firm action. This showed a civil servant of great stature.

He was an excellent host too. I remember how meticulous and elegant he was at an exclusive dinner he had hosted in Odisha Bhavan for Rose Millian Bathew Kharbuli, then Chairman of UPSC. Incidentally, she was the first lady to hold that post. He himself had planned everything, ranging from the menu, the décor of the dining room, the invitees. The staff of the guest house responded in adequate measures and the culinary skill displayed by them was just amazing. He saw off the guest closing the door of her car she had been ushered in to with great respect. I also remember an elegant party he had hosted to celebrate (IAS officer) Vivek Pattanayak’s appointment in the ICAO, Montreal.

Once I suggested to him to write a book on governance based on his experience. He smiled and in his usual style of humour recounted the travails of a writer. “You take the trouble of writing, then slog to get the manuscript converted to DTP, then look for a publisher and then become a salesman selling or gifting the book,” he said and laughed. The next moment he was serious and said, “I don’t possess the extraordinary merit nor have I propounded anything new and revolutionary to write about. My efforts have been to get things done with professional rectitude.”

Here was a civil servant who believed in Yogah Karmasu Kaushalam (Yoga is excellence at work).

Another incident comes to my mind. He was trying to teach me the role of senior officers in grooming juniors and recounted an experience with my father. R N Das was the Collector of Keonjhar and my father, as Secretary to a Department, was touring his district. The young Collector had taken some decisions in good faith but without government orders and sought the senior’s guidance. The Secretary asked for the file from the collectorate and recorded his approval on the spot.

His most noteworthy contribution was in protecting the primacy of the institution of Chief Secretary against malware attacks. The legacy continued for some years. He had added speed to the slow bureaucracy. He was a healthy link between the political boss and the bureaucracy. He always remained a protective umbrella to the officialdom against the headwind, rain and hot sun.

He loved to be amidst his colleagues. Even when he was not too well, he remained active in the WhatsApp Group of IAS officers and would continue to counsel, crack jokes, exchange pleasantries. In his passing away, we lost a distinguished civil servant.